Optimizing Scripts

This section demonstrates how you would go about optimizing the actual scripts and methods your game uses, and it also goes into detail about the reasons why the optimizations work, and why applying them will benefit you in certain situations.

Profiler is King

There is no such thing as a list of boxes to check that will ensure your project runs smoothly. To optimize a slow project, you have to profile to find specific offenders that take up a disproportionate amount of time. Trying to optimize without profiling or without thoroughly understanding the results that the profiler gives is like trying to optimize with a blindfold on.

Internal mobile profiler

You can use the internal profiler to figure out what kind of process is slowing your game down, be it physics, scripts, or rendering, but you can’t drill down into specific scripts and methods to find the actual offenders. However, by building switches into your game which enable and disable certain functionality, you can narrow down the worst offenders significantly. For example, if you remove the enemy characters’ AI script and the framerate doubles, you know that the script, or something that it brings into the game, has to be optimized. The only problem is that you may have to try a lot of different things before you find the problem.

For more about profiling on mobile devices, see the profiling section.

Optimized by Design

Attempting to develop something which is fast from the beginning is risky, because there is a trade-off between wasting time making things that would be just as fast if they weren’t optimized and making things which will have to be cut or replaced later because they are too slow. It takes intuition and knowledge of the hardware to make good decisions in this regard, especially because every game is different and what might be a crucial optimization for one game may be a flop in another.

Object Pooling

We gave object pooling as an example of the intersection between good gameplay and good code design in the introduction to optimized scripting methods. Using object pooling for ephemeral objects is faster than creating and destroying them, because it makes memory allocation simpler and removes dynamic memory allocation overhead and Garbage Collection, or GC.

Memory Allocation

Simple Explanation of what Automatic Memory Management is

Scripts you write in Unity use automatic memory management. Just about all scripting languages do this. In contrast, lower level languages such as C and C++ use manual memory allocation, where the programmer is allowed to read and write from memory addresses directly, and as a consequence they are responsible for removing every object they create. For example, if you create objects in your C++, you have to manually de-allocate the memory that they take up when you are done with them. In a scripting language, it is enough to say objectReference = null;

Note: If I have a game object variable like GameObject myGameObject; or var myGameObject : GameObject;, why isn’t it destroyed when I say myGameObject = null;?

- The game object is still referenced by Unity, because Unity has to maintain a reference to it in order for it to be drawn, updated, etc. Calling

Destroy(myGameObject);removes that reference and deletes the object.

But if you create an object that Unity has no idea about, for example, an instance of a class that does not inherit from anything (in contrast, most classes or “script components” inherit from MonoBehaviour) and then set your reference variable to it to null, what actually happens is that the object is lost as far as your script and Unity are concerned; they can’t access it and will never see it again, but it stays in memory. Then, some time later, the Garbage Collector runs, and it removes anything in memory that is not referenced anywhere. It is able to do this because, behind the scenes, the number of references to each block of memory is kept track of. This is one reason why scripting languages are slower than C++.

- Read more about Automatic Memory Management and the Garbage Collector.

How to Avoid Allocating Memory

Every time an object is created, memory is allocated. Very often in code, you are creating objects without even knowing it.

-

Debug.Log("boo" + "hoo");creates an object.- Use

System.String.Emptyinstead of""when dealing with lots of strings.

- Use

- Immediate Mode GUI (UnityGUI) is slow and should not be used at any time when performance is an issue.

- Difference between class and struct:

Classes are objects and behave as references. If Foo is a class and

Foo foo = new Foo();

MyFunction(foo);

then MyFunction will receive a reference to the original Foo object that was allocated on the heap. Any changes to foo inside MyFunction will be visible anywhere foo is referenced.

Classes are data and behave as such. If Foo is a struct and

Foo foo = new Foo();

MyFunction(foo);

then MyFunction will receive a copy of foo. foo is never allocated on the heap and never garbage collected. If MyFunction modifies it’s copy of foo, the other foo is unaffected.

- Objects which stick around for a long time should be classes, and objects which are ephemeral should be structs. Vector3 is probably the most famous struct. If it were a class, everything would be a lot slower.

Why Object Pooling is Faster

The upshot of this is that using Instantiate and Destroy a lot gives the Garbage Collector a lot to do, and this can cause a “hitch” in gameplay. As the Automatic Memory Management page explains, there are other ways to get around the common performance hitches that surround Instantiate and Destroy, such as triggering the Garbage Collector manually when nothing is going on, or triggering it very often so that a large backlog of unused memory never builds up.

Another reason is that, when a specific prefab is instantiated for the first time, sometimes additional things have to be loaded into RAM, or textures and meshes need to be uploaded to the GPU. This can cause a hitch as well, and with object pooling, this happens when the level loads instead of during gameplay.

Imagine a puppeteer who has an infinite box of puppets, where every time the script calls for a character to appear, they get a new copy of its puppet out of the box, and every time the character exits the stage, they toss the current copy. Object pooling is the equivalent of getting all the puppets out of the box before the show starts, and leaving them on the table behind the stage whenever they are not supposed to be visible.

Why Object Pooling can be Slower

One issue is that the creation of a pool reduces the amount of heap memory available for other purposes; so if you keep allocating memory on top of the pools you just created, you might trigger garbage collection even more often. Not only that, every collection will be slower, because the time taken for a collection increases with the number of live objects. With these issues in mind, it should be apparent that performance will suffer if you allocate pools that are too large or keep them active when the objects they contain will not be needed for some time. Furthermore, many types of objects don’t lend themselves well to object pooling. For example, the game may include spell effects that persist for a considerable time or enemies that appear in large numbers but which are only killed gradually as the game progresses. In such cases, the performance overhead of an object pool greatly outweighs the benefits and so it should not be used.

Implementation

Here’s a simple side by side comparison of a script for a simple projectile, one using Instantiation, and one using Object Pooling.

// GunWithInstantiate.js // GunWithObjectPooling.js

#pragma strict #pragma strict

var prefab : ProjectileWithInstantiate; var prefab : ProjectileWithObjectPooling;

var maximumInstanceCount = 10;

var power = 10.0; var power = 10.0;

private var instances : ProjectileWithObjectPooling[];

static var stackPosition = Vector3(-9999, -9999, -9999);

function Start () {

instances = new ProjectileWithObjectPooling[maximumInstanceCount];

for(var i = 0; i < maximumInstanceCount; i++) {

// place the pile of unused objects somewhere far off the map

instances[i] = Instantiate(prefab, stackPosition, Quaternion.identity);

// disable by default, these objects are not active yet.

instances[i].enabled = false;

}

}

function Update () { function Update () {

if(Input.GetButtonDown("Fire1")) { if(Input.GetButtonDown("Fire1")) {

var instance : ProjectileWithInstantiate = var instance : ProjectileWithObjectPooling = GetNextAvailiableInstance();

Instantiate(prefab, transform.position, transform.rotation); if(instance != null) {

instance.velocity = transform.forward * power; instance.Initialize(transform, power);

} }

} }

}

function GetNextAvailiableInstance () : ProjectileWithObjectPooling {

for(var i = 0; i < maximumInstanceCount; i++) {

if(!instances[i].enabled) return instances[i];

}

return null;

}

// ProjectileWithInstantiate.js // ProjectileWithObjectPooling.js

#pragma strict #pragma strict

var gravity = 10.0; var gravity = 10.0;

var drag = 0.01; var drag = 0.01;

var lifetime = 10.0; var lifetime = 10.0;

var velocity : Vector3; var velocity : Vector3;

private var timer = 0.0; private var timer = 0.0;

function Initialize(parent : Transform, speed : float) {

transform.position = parent.position;

transform.rotation = parent.rotation;

velocity = parent.forward * speed;

timer = 0;

enabled = true;

}

function Update () { function Update () {

velocity -= velocity * drag * Time.deltaTime; velocity -= velocity * drag * Time.deltaTime;

velocity -= Vector3.up * gravity * Time.deltaTime; velocity -= Vector3.up * gravity * Time.deltaTime;

transform.position += velocity * Time.deltaTime; transform.position += velocity * Time.deltaTime;

timer += Time.deltaTime; timer += Time.deltaTime;

if(timer > lifetime) { if(timer > lifetime) {

transform.position = GunWithObjectPooling.stackPosition;

Destroy(gameObject); enabled = false;

} }

} }

Of course, for a large, complicated game, you will want to make a generic solution that works for all your prefabs.

Another Example: Coin Party!

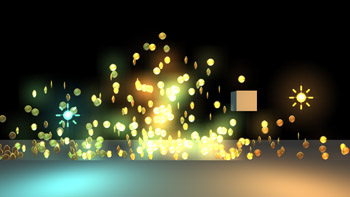

The example of “Hundreds of rotating, dynamically lit, collectable coins onscreen at once” which was given in the Scripting Methods section will be used to demonstrate how script code, Unity components like the Particle System, and custom shaders can be used to create a stunning effect without taxing the weak mobile hardware.

Imagine that this effect lives in the context of a 2D sidescrolling game with tons of coins that fall, bounce, and rotate. The coins are dynamically lit by point lights. We want to capture the light glinting off the coins to make our game more impressive.

If we had powerful hardware, we could use a standard approach to this problem. Make every coin an object, shade the object with either vertex-lit, forward, or deferred lighting, and then add glow on top as an image effect to get the brightly reflecting coins to bleed light onto the surrounding area.

But mobile hardware would choke on that many objects, and a glow effect is totally out of the question. So what do we do?

Animated Sprite Particle System

If you want to display a lot of objects which all move in a similar way and can never be carefully inspected by the player, you might be able to render large amounts of them in no time using a particle system. Here are a few stereotypical applications of this technique:

- Collectables or Coins

- Flying Debris

- Hordes or Flocks of Simple Enemies

- Cheering Crowds

- Hundreds of Projectiles or Explosions

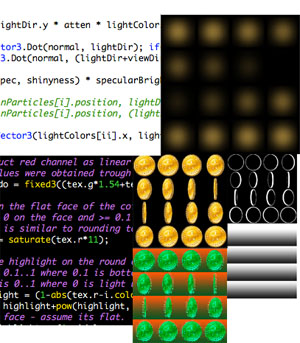

There is a free editor extension called Sprite Packer that facilitates the creation of animated sprite particle systems. It renders frames of your object to a texture, which can then be used as an animated sprite sheet on a particle system. For our use case, we would use it on our rotating coin.

Reference Implementation

Included in the Sprite Packer project is an example that demonstrates a solution to this exact problem.

It uses a family of assets of all different kinds to achieve a dazzling effect on a low computing budget:

- A control script

- Specialized textures created from the output of the SpritePacker

- A specialized shader which is intimately connected with both the control script and the texture.

A readme file is included with the example which attempts to explain why and how the system works, outlining the process that was used to determine what features were needed and how they were implemented. This is that file:

The problem was defined as “Hundreds of rotating, dynamically lit, collectable coins onscreen at once.”

The naive approach is to Instantiate a bunch of copies of a coin prefab, but instead we are going to use particles to render our coins. However, this introduces a number of challenges that we have to overcome.

- Viewing angles are a problem because particles don’t have them.

- We assume that the camera stays right-side up and the coins rotate around the Y-axis.

- We create the illusion of coin rotation with an animated texture that we packed using the SpritePacker.

- This introduces a new problem: Monotony of rotating coins all rotating at the same speed and in the same direction

- We keep track of rotation and lifetime ourselves and “render” rotation to the particle lifetimes in script to fix this.

- Normals are a problem because particles don’t have them, and we need real time lighting.

- Generate a single normal vector for the face of the coin in each animation frame generated by the Sprite Packer.

- Do Blinn-Phong lighting for each particle in script, based on the normal vector grabbed from the above list.

- Apply the result to the particle as a color.

- Handle the face of the coin and the rim of the coin separately in the shader.

Introduces a new problem: How does the shader know where the rim is, and what part of the rim it’s on?

- Can’t use UV’s, they are already used for the animation.

- Use a texture map.

- Need Y-position relative to coin.

- Need binary “on face” vs “on rim”.

- We don’t want to introduce another texture, more texture reads, more texture memory.

- Combine needed information into one channel and replace one of the texture’s color channels with it.

- Now our coin is the wrong color! What do we do?

- Use the shader to reconstruct missing channel as a combination of the two remaining channels.

- Say we want glow from light glinting off our coins. Post process is too expensive for mobile devices.

- Create another particle system and give it a softened, glowy version of the coin animation.

- Color a glow only when the corresponding coin’s color is super bright.

- Can’t have glow rendered on every coin every frame - fill rate killer.

- Reset glows every frame, only position ones with brightness > 0.

- Physics is a problem, collecting coins is a problem - particles don’t collide very well.

- Could use built-in particle collision?

- Instead, just wrote collision into the script.

- Finally, we have one more problem - this script does a lot, and its getting slow!

- Performance scales linearly with number of active coins.

- Limit maximum coins. This works well enough to acheive our goal: 100 coins, 2 lights, runs really fast on mobile devices.

- Performance scales linearly with number of active coins.

- Things to try to optimize further:

- Instead of calculating lighting for every coin individually, cut the world into chunks and calculate lighting conditions for every rotation frame in every chunk.

- Use as a lookup table with coin position and coin rotation as indices.

- Increase fidelity by using bilinear interpolation with position.

- Sparse updates on the lookup table, or, entirely static lookup table.

- Use Light Probes for this? *Instead of calculating lighting in script, use normal-mapped particles?

- Use “Display Normals” shader to bake frame animation of normals.

- Limits number of lights.

- Fixes slow script problem.

- Instead of calculating lighting for every coin individually, cut the world into chunks and calculate lighting conditions for every rotation frame in every chunk.

The end goal of this example or “moral of the story” is that if there is something which your game really needs, and it causes lag when you try to achieve it through conventional means, that doesn’t mean that it is impossible, it just means that you have to put in some work on a system of your own that runs much faster.

Techniques for Managing Thousands of Objects

These are specific scripting optimizations which are applicable in situations where hundreds or thousands of dynamic objects are involved. Applying these techniques to every script in your game is a terrible idea; they should be reserved as tools and design guidelines for large scripts which handle tons of objects or data at run time.

Avoid or minimize O(n2) operations on large data sets

In computer science, the Order of an operation, denoted by O(n), refers to the way that the number of times that the operation has to be evaluated increases as the number of objects it is applied to (n) increases.

For example, consider a basic sorting algorithm. I have n numbers and I want to sort them from smallest to largest.

void sort(int[] arr) {

int i, j, newValue;

for (i = 1; i < arr.Length; i++) {

// record

newValue = arr[i];

//shift everything that is larger to the right

j = i;

while (j > 0 && arr[j - 1] > newValue) {

arr[j] = arr[j - 1];

j--;

}

// place recorded value to the left of large values

arr[j] = newValue;

}

}

The important part is that there are two loops here, one inside the other.

for (i = 1; i < arr.Length; i++) {

...

j = i;

while (j > 0 && arr[j - 1] > newValue) {

...

j--;

}

}

Let’s assume that we give the algorithm the worst possible case: the input numbers are sorted, but in reverse order. In that case, the innermost loop will run j times. On average, as i goes from 1 to arr.Length–1, j will be arr.Length/2. In terms of O(n), arr.Length is our n, so, in total, the innermost loop runs nn/2* times, or n2/2** times. But in O(n) terms, we chuck all constants like 1/2, because we want to talk about the way that the number of operations increases, not the actual number of operations. So the algorithm is O(n2). The order of an operation matters a lot if the data set is large, because the number of operations can explode exponentially.

An in-game example of an O(n2) operation is 100 enemies, where the AI of each enemy takes the movements of every other enemy into account. It might be faster to divide the map into cells, record the movement of each enemy into the nearest cell, and then have each enemy sample the nearest few cells. That would be an O(n) operation.

Cache references instead of performing unnecessary searches

Say you have 100 enemies in your game, and they all move towards the player.

// EnemyAI.js

var speed = 5.0;

function Update () {

transform.LookAt(GameObject.FindWithTag("Player").transform);

// this would be even worse:

//transform.LookAt(FindObjectOfType(Player).transform);

transform.position += transform.forward * speed * Time.deltaTime;

}

That could be slow, if there are enough of them running at the same time. Little known fact: all of the component accessors in MonoBehaviour, things like transform, renderer, and audio, are equivalent to their GetComponent(Transform) counterparts, and they are actually a bit slow. GameObject.FindWithTag has been optimized, but in some cases, for example, in inner loops, or on scripts that run on a lot of instances, this script might be a bit slow.

This is a better version of the script.

// EnemyAI.js

var speed = 5.0;

private var myTransform : Transform;

private var playerTransform : Transform;

function Start () {

myTransform = transform;

playerTransform = GameObject.FindWithTag("Player").transform;

}

function Update () {

myTransform.LookAt(playerTransform);

myTransform.position += myTransform.forward * speed * Time.deltaTime;

}

Minimize expensive math functions

Transcendental functions (Mathf.Sin, Mathf.Pow, etc), Division, and Square Root all take about 100x the time of a multiplication. (In the grand scheme of things, no time at all, but if you are calling them thousands of times per frame it can add up).

The most common case of this is vector normalization. If you are normalizing the same vector over and over, consider normalizing it once instead and caching the result for use later.

If you are both using the length of a vector and normalizing it, it would be faster to obtain the normalized vector by multiplying the vector by the reciprocal of the length rather than by using the .normalized property.

If you are comparing distances, you don’t have to compare the actual distances. You can compare the squares of the distances instead by using the .sqrMagnitude property and save a square root or two.

Another one, if you are dividing over and over by a constant c, you can multiply by the reciprocal instead. Calculate the reciprocal first by doing 1.0/c.

Only execute expensive operations occasionally, e.g. Physics.Raycast()

If you have to do something expensive, you might be able to optimize it by doing it less often and caching the result. For example, consider a projectile script that uses Raycast:

// Bullet.js

var speed = 5.0;

function FixedUpdate () {

var distanceThisFrame = speed * Time.fixedDeltaTime;

var hit : RaycastHit;

// every frame, we cast a ray forward from where we are to where we will be next frame

if(Physics.Raycast(transform.position, transform.forward, hit, distanceThisFrame)) {

// Do hit

} else {

transform.position += transform.forward * distanceThisFrame;

}

}

Right away, we could improve the script by replacing FixedUpdate with Update and fixedDeltaTime with deltaTime. FixedUpdate refers to the Physics update, which happens more often than the frame update. But let’s go even further by only raycasting every n seconds. A smaller n gives greater temporal resolution, and a bigger n gives better performance. The bigger and slower your targets are, the bigger n can be before temporal aliasing occurs. (Appearance of latency, where the player hit the target, but the explosion appears where the target used to be n seconds ago, or the player hit the target, but the projectile goes right through).

// BulletOptimized.js

var speed = 5.0;

var interval = 0.4; // this is 'n', in seconds.

private var begin : Vector3;

private var timer = 0.0;

private var hasHit = false;

private var timeTillImpact = 0.0;

private var hit : RaycastHit;

// set up initial interval

function Start () {

begin = transform.position;

timer = interval+1;

}

function Update () {

// don't allow an interval smaller than the frame.

var usedInterval = interval;

if(Time.deltaTime > usedInterval) usedInterval = Time.deltaTime;

// every interval, we cast a ray forward from where we were at the start of this interval

// to where we will be at the start of the next interval

if(!hasHit && timer >= usedInterval) {

timer = 0;

var distanceThisInterval = speed * usedInterval;

if(Physics.Raycast(begin, transform.forward, hit, distanceThisInterval)) {

hasHit = true;

if(speed != 0) timeTillImpact = hit.distance / speed;

}

begin += transform.forward * distanceThisInterval;

}

timer += Time.deltaTime;

// after the Raycast hit something, wait until the bullet has traveled

// about as far as the ray traveled to do the actual hit

if(hasHit && timer > timeTillImpact) {

// Do hit

} else {

transform.position += transform.forward * speed * Time.deltaTime;

}

}

Minimize callstack overhead in inner loops

Just calling a function has a little bit of overhead in itself. If you are calling things like x = Mathf.Abs(x) thousands of times per frame, it might be better to just do x = (x > 0 ? x : -x); instead.

Optimizing Physics Performance

The NVIDIA PhysX physics engine used by Unity is available on mobiles, but the performance limits of the hardware will be reached more easily on mobile platforms than desktops.

Here are some tips for tuning physics to get better performance on mobiles:-

- You can adjust the Fixed Timestep setting (in the Time manager) to reduce the time spent on physics updates. Increasing the timestep will reduce the CPU overhead at the expense of the accuracy of the physics. Often, lower accuracy is an acceptable tradeoff for increased speed.

- Set the Maximum Allowed Timestep in the Time manager in the 8–10fps range to cap the time spent on physics in the worst case scenario.

- Mesh colliders have a much higher performance overhead than primitive colliders, so use them sparingly. It is often possible to approximate the shape of a mesh by using child objects with primitive colliders. The child colliders will be controlled collectively as a single compound collider by the rigidbody on the parent.

- While wheel colliders are not strictly colliders in the sense of solid objects, they nonetheless have a high CPU overhead.

Did you find this page useful? Please give it a rating: