Manual

- Unity User Manual (2020.1)

- Packages

- Verified packages

- 2D Animation

- 2D Pixel Perfect

- 2D PSD Importer

- 2D SpriteShape

- Adaptive Performance

- Adaptive Performance Samsung Android

- Addressables

- Advertisement

- Alembic

- Analytics Library

- Android Logcat

- AR Foundation

- ARCore XR Plugin

- ARKit Face Tracking

- ARKit XR Plugin

- Burst

- Cinemachine

- Editor Coroutines

- High Definition RP

- In App Purchasing

- Input System

- JetBrains Rider Editor

- Magic Leap XR Plugin

- ML Agents

- Mobile Notifications

- Multiplayer HLAPI

- Oculus XR Plugin

- Polybrush

- Post Processing

- ProBuilder

- Profile Analyzer

- Quick Search

- Remote Config

- Scriptable Build Pipeline

- Shader Graph

- Test Framework

- TextMeshPro

- Timeline

- Unity Collaborate

- Unity Distribution Portal

- Unity Recorder

- Universal RP

- Visual Effect Graph

- Visual Studio Code Editor

- Visual Studio Editor

- Windows XR Plugin

- Xiaomi SDK

- XR Plugin Management

- Preview packages

- Core packages

- Built-in packages

- AI

- Android JNI

- Animation

- Asset Bundle

- Audio

- Cloth

- Director

- Image Conversion

- IMGUI

- JSONSerialize

- Particle System

- Physics

- Physics 2D

- Screen Capture

- Terrain

- Terrain Physics

- Tilemap

- UI

- UIElements

- Umbra

- Unity Analytics

- Unity Web Request

- Unity Web Request Asset Bundle

- Unity Web Request Audio

- Unity Web Request Texture

- Unity Web Request WWW

- Vehicles

- Video

- VR

- Wind

- XR

- Packages by keywords

- Unity's Package Manager

- Creating custom packages

- Verified packages

- Working in Unity

- Installing Unity

- Upgrading Unity

- Using the API Updater

- Upgrading to Unity 2020.2

- Upgrading to Unity 2020.1

- Upgrading to Unity 2019 LTS

- Upgrading to Unity 2018 LTS

- Legacy Upgrade Guides

- Unity's interface

- Asset workflow

- Создание геймплея.

- Editor Features

- 2D and 3D mode settings

- Preferences

- Presets

- Shortcuts Manager

- Build Settings

- Project Settings

- Visual Studio C# integration

- RenderDoc Integration

- Using the Xcode frame debugger

- Editor Analytics

- Проверка обновлений

- IME в Unity

- Специальные Папки Проекта

- Reusing Assets between Projects

- Version Control

- Multi-Scene editing

- Command line arguments

- Support for custom Menu Item and Editor features

- Text-Based Scene Files

- Решение проблем в редакторе

- Analysis

- Importing

- Input

- 2D

- Геймплей в 2D

- 2D Sorting

- Sprites

- Tilemap

- Physics Reference 2D

- Графика

- Render pipelines

- Built-in Render Pipeline

- Universal Render Pipeline

- High Definition Render Pipeline

- Scriptable Render Pipeline

- Scriptable Render Pipeline introduction

- Creating a custom Scriptable Render Pipeline

- Creating a Render Pipeline Asset and Render Pipeline Instance

- Setting the active Render Pipeline Asset

- Creating a simple render loop in a custom Scriptable Render Pipeline

- Scheduling and executing rendering commands in the Scriptable Render Pipeline

- Scriptable Render Pipeline (SRP) Batcher

- Cameras

- Post-processing

- Lighting

- Introduction to lighting

- Light sources

- Shadows

- The Lighting window

- Lighting Settings Asset

- The Light Explorer window

- Lightmapping

- The Progressive Lightmapper

- Lightmapping using Enlighten (deprecated)

- Lightmapping: Getting started

- Lightmap Parameters Asset

- Directional Mode

- Lightmaps and LOD

- Ambient occlusion

- Lightmaps: Technical information

- Lightmapping and the Shader Meta Pass

- Lightmap UVs

- UV overlap

- Lightmap seam stitching

- Custom fall-off

- Realtime Global Illumination using Enlighten (deprecated)

- Light Probes

- Reflection Probes

- Precomputed lighting data

- Scene View Draw Modes for lighting

- Meshes, Materials, Shaders and Textures

- Mesh Components

- Materials

- Текстуры

- Writing Shaders

- Standard Shader

- Standard Particle Shaders

- Autodesk Interactive shader

- Legacy Shaders

- Shader Reference

- Writing Surface Shaders

- Writing vertex and fragment shaders

- Примеры вершинных и фрагментных шейдеров

- Shader semantics

- Accessing shader properties in Cg/HLSL

- Providing vertex data to vertex programs

- Встроенные подключаемые файлы для шейдеров

- Стандартные шейдерные предпроцессорные макросы

- Built-in shader helper functions

- Built-in shader variables

- Shader variants and keywords

- GLSL Shader programs

- Shading language used in Unity

- Shader Compilation Target Levels

- Shader data types and precision

- Using sampler states

- Синтаксис ShaderLab: Shader

- Синтаксис ShaderLab: свойства

- Синтаксис ShaderLab: SubShader

- Синтаксис ShaderLab: Pass

- ShaderLab culling and depth testing

- Синтаксис ShaderLab: Blending

- Синтаксис ShaderLab: тэги Pass

- Синтаксис ShaderLab: Stencil

- Синтаксис ShaderLab: Name

- Синтаксис ShaderLab: цвет, материал, освещение

- ShaderLab: Legacy Texture Combiners

- Синтакс ShaderLab: Альфа тестинг (Alpha testing)

- Синтаксис ShaderLab: туман

- Синтаксис ShaderLab: BindChannels

- Синтаксис ShaderLab: UsePass

- Синтаксис ShaderLab: GrabPass

- ShaderLab: SubShader Tags

- Синтаксис ShaderLab: Pass

- Синтаксис ShaderLab: Fallback

- #Синтаксис ShaderLab: CustomEditor

- Синтаксис ShaderLab: другие команды

- Shader assets

- Расширенные возможности ShaderLab

- Optimizing shader variants

- Asynchronous Shader compilation

- Performance tips when writing shaders

- Rendering with Replaced Shaders

- Custom Shader GUI

- Использование текстур глубины

- Текстура глубины камеры

- Особенности рендеринга различных платформ

- ShaderLab: SubShader LOD value

- Using texture arrays in shaders

- Debugging DirectX 11/12 shaders with Visual Studio

- Debugging DirectX 12 shaders with PIX

- Implementing Fixed Function TexGen in Shaders

- Tutorial: ShaderLab and fixed function shaders

- Tutorial: vertex and fragment programs

- Particle systems

- Choosing your particle system solution

- Built-in Particle System

- Using the Built-in Particle System

- Particle System vertex streams and Standard Shader support

- Particle System GPU Instancing

- Particle System C# Job System integration

- Components and Modules

- Particle System

- Particle System modules

- Particle System Main module

- Emission module

- Shape Module

- Velocity over Lifetime module

- Noise module

- Limit Velocity Over Lifetime module

- Inherit Velocity module

- Lifetime by Emitter Speed

- Force Over Lifetime module

- Color Over Lifetime module

- Color By Speed module

- Size over Lifetime module

- Size by Speed module

- Rotation Over Lifetime module

- Rotation By Speed module

- External Forces module

- Collision module

- Triggers module

- Sub Emitters module

- Texture Sheet Animation module

- Lights module

- Trails module

- Custom Data module

- Renderer module

- Particle System Force Field

- Built-in Particle System examples

- Visual Effect Graph

- Creating environments

- Sky

- Visual Effects Components

- Advanced rendering features

- High dynamic range

- Level of Detail (LOD) for meshes

- Graphics API support

- Streaming Virtual Texturing

- Streaming Virtual Texturing requirements and compatibility

- How Streaming Virtual Texturing works

- Enabling Streaming Virtual Texturing in your project

- Using Streaming Virtual Texturing in Shader Graph

- Cache Management for Virtual Texturing

- Marking textures as "Virtual Texturing Only"

- Virtual Texturing error material

- Compute shaders

- GPU instancing

- Делимые текстуры (Sparse Textures)

- CullingGroup API

- Loading texture and mesh data

- Оптимизация производительности графики

- Color space

- Graphics tutorials

- Как мне исправить вращение импортированной модели?

- Art Asset best practice guide

- Importing models from 3D modeling software

- Making believable visuals in Unity

- Update: believable visuals in URP and HDRP

- Believable visuals: preparing assets

- Believable visuals: render settings

- Believable visuals: lighting strategy

- Believable visuals: models

- Believable visuals: materials and shaders

- Believable visuals: outdoor lighting

- Believable visuals: indoor and local lighting

- Believable visuals: post-processing

- Believable visuals: dynamic lighting

- Setting up the Rendering Pipeline and Lighting in Unity

- Render pipelines

- Physics

- Scripting

- Setting Up Your Scripting Environment

- Scripting concepts

- Important Classes

- Important Classes - GameObject

- Important Classes - MonoBehaviour

- Important Classes - Object

- Important Classes - Transform

- Important Classes - Vectors

- Important Classes - Quaternion

- ScriptableObject

- Important Classes - Time and Framerate Management

- Important Classes - Mathf

- Important Classes - Random

- Important Classes - Debug

- Important Classes - Gizmos & Handles

- Unity architecture

- Plug-ins

- C# Job System

- Multiplayer and Networking

- Multiplayer Overview

- Setting up a multiplayer project

- Using the Network Manager

- Using the Network Manager HUD

- The Network Manager HUD in LAN mode

- The Network Manager HUD in Matchmaker mode

- Converting a single-player game to Unity Multiplayer

- Debugging Information

- The Multiplayer High Level API

- Multiplayer Component Reference

- Multiplayer Classes Reference

- Multiplayer Encryption Plug-ins

- UnityWebRequest

- Аудио

- Аудио. Обзор.

- Аудио файлы

- Трекерные модули

- Audio Mixer

- Native Audio Plugin SDK

- Audio Profiler

- Ambisonic Audio

- Справочник по аудио

- Audio Clip

- Audio Listener

- Audio Source

- Audio Mixer

- Аудио эффекты (только для Pro версии)

- Audio Effects

- Audio Low Pass Effect

- Audio High Pass Effect

- Audio Echo Effect

- Audio Flange Effect

- Audio Distortion Effect

- Audio Normalize Effect

- Audio Parametric Equalizer Effect

- Audio Pitch Shifter Effect

- Audio Chorus Effect

- Audio Compressor Effect

- Audio SFX Reverb Effect

- Audio Low Pass Simple Effect

- Audio High Pass Simple Effect

- Reverb Zones

- Микрофон

- Audio Settings

- Video overview

- Анимация

- Animation System Overview

- Анимационные клипы

- Animator Controllers (контроллеры аниматоров)

- Аниматор и контроллер аниматора

- The Animator Window

- Конечные автоматы в анимации

- Blend Trees (Деревья смешивания)

- Working with blend shapes

- Animator Override Controllers

- Переназначение гуманоидных анимаций

- Performance and optimization

- Animation Reference

- Кривые анимации и события

- Playables API

- Словарь терминов анимации и Mecanim.

- Creating user interfaces (UI)

- Comparison of UI systems in Unity

- UI Toolkit

- Unity UI

- Сanvas (Полотно)

- Basic Layout

- Визуальные компоненты

- Компоненты взаимодействия

- Animation Integration

- Auto Layout

- Rich Text

- Event System

- Справка по пользовательским интерфейсам

- Rect Transform

- Canvas Components

- Visual Components

- Interaction Components

- Auto Layout

- Справка по системе событий

- Практические рекомендации по работе с UI (пользовательскими интерфейсами)

- Immediate Mode GUI (IMGUI)

- Навигация и поиск пути

- Navigation Overview

- Navigation System in Unity

- Inner Workings of the Navigation System

- Building a NavMesh

- NavMesh building components

- Advanced NavMesh Bake Settings

- Creating a NavMesh Agent

- Creating a NavMesh Obstacle

- Creating an Off-mesh Link

- Building Off-Mesh Links Automatically

- Building Height Mesh for Accurate Character Placement

- Navigation Areas and Costs

- Loading Multiple NavMeshes using Additive Loading

- Using NavMesh Agent with Other Components

- Справочник по навигации

- Navigation How-Tos

- Navigation Overview

- Unity Services

- Setting up your project for Unity services

- Unity Organizations

- Unity Ads

- Unity Analytics

- Unity Analytics Overview

- Setting Up Analytics

- Analytics Dashboard

- Analytics events

- Funnels

- Remote Settings

- Unity Analytics A/B Testing

- Monetization

- User Attributes

- Unity Analytics Raw Data Export

- Data reset

- Upgrading Unity Analytics

- COPPA Compliance

- Unity Analytics and the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

- Analytics Metrics, Segments, and Terminology

- Unity Cloud Build

- Automated Build Generation

- Supported platforms

- Supported versions of Unity

- Share links

- Version control systems

- Using the Unity Developer Dashboard to configure Unity Cloud Build for Git

- Using the Unity Developer Dashboard to configure Unity Cloud Build for Mercurial

- Using Apache Subversion (SVN) with Unity Cloud Build

- Using the Unity Developer Dashboard to configure Unity Cloud Build for Perforce

- Using the Unity Developer Dashboard to configure Unity Cloud Build for Plastic

- Building for iOS

- Advanced options

- Using Addressables in Unity Cloud Build

- Build manifest

- Scheduled builds

- Cloud Build REST API

- Unity Cloud Content Delivery

- Unity IAP

- Setting up Unity IAP

- Cross Platform Guide

- Codeless IAP

- Defining products

- Subscription Product support

- Initialization

- Browsing Product Metadata

- Initiating Purchases

- Processing Purchases

- Handling purchase failures

- Restoring Transactions

- Purchase Receipts

- Receipt validation

- Store Extensions

- Cross-store installation issues with Android in-app purchase stores

- Store Guides

- Implementing a Store

- Unity Collaborate

- Setting up Unity Collaborate

- Adding team members to your Unity project

- Viewing history

- Enabling Cloud Build with Collaborate

- Managing Unity Editor versions

- Reverting files

- Resolving file conflicts

- Excluding Assets from publishing to Collaborate

- Publishing individual files to Collaborate

- Restoring previous versions of a project

- In-Progress edit notifications

- Managing cloud storage

- Moving your Project to another version control system

- Unity Accelerator

- Collaborate troubleshooting tips

- Unity Cloud Diagnostics

- Unity Integrations

- Multiplayer Services

- Unity Distribution Portal

- XR

- Getting started with AR development in Unity

- Getting started with VR development in Unity

- XR Plug-in Framework

- Configuring your Unity Project for XR

- Universal Render Pipeline compatibility in XR

- XR API reference

- Single Pass Stereo rendering (Double-Wide rendering)

- VR Audio Spatializers

- VR frame timing

- Unity XR SDK

- Open-source repositories

- Asset Store Publishing

- Creating your Publisher Account

- Creating a new package draft

- Deleting a package draft

- Uploading Assets to your package

- Filling in the package details

- Submitting your package for approval

- Viewing the status of your Asset Store submissions

- Collecting revenue

- Providing support to your customers

- Adding tags to published packages

- Connecting your account to Google Analytics

- Promoting your Assets

- Refunding your customers

- Upgrading packages

- Deprecating your Assets

- Issuing vouchers

- Managing your publishing team

- Asset Store Publisher portal

- Platform development

- Using Unity as a Library in other applications

- Enabling deep linking

- Автономный

- macOS

- Apple TV

- WebGL

- Getting started with WebGL development

- WebGL Player settings

- Building and running a WebGL project

- WebGL: Compressed builds and server configuration

- WebGL: Server configuration code samples

- WebGL Browser Compatibility

- WebGL Graphics

- Using Audio In WebGL

- Embedded Resources on WebGL

- Using WebGL templates

- Cursor locking and full-screen mode in WebGL

- Input in WebGL

- WebGL: Interacting with browser scripting

- WebGL performance considerations

- Memory in WebGL

- Debugging and troubleshooting WebGL builds

- WebGL Networking

- Getting started with WebGL development

- iOS

- Integrating Unity into native iOS applications

- Первые шаги в iOS разработке

- iOS build settings

- iOS Player settings

- Продвинутые темы по iOS

- Troubleshooting on iOS devices

- Сообщение об ошибках, приводящих к "падениям" на iOS

- Android

- Android environment setup

- Integrating Unity into Android applications

- Unity Remote

- Android Player settings

- Android Keystore Manager

- Building apps for Android

- Single-Pass Stereo Rendering for Android

- Building and using plug-ins for Android

- Android mobile scripting

- Troubleshooting Android development

- Reporting crash bugs under Android

- Windows

- Integrating Unity into Windows and UWP applications

- Windows General

- Universal Windows Platform

- Приложения Windows Store: Приступая к работе

- Universal Windows Platform: Deployment

- Universal Windows Platform (UWP) build settings

- Windows Device Portal Deployment

- Universal Windows Platform: Profiler

- Universal Windows Platform: Command line arguments

- Universal Windows Platform: Association launching

- Класс AppCallbacks

- Universal Windows Platform: WinRT API in C# scripts

- Universal Windows Platform Player Settings

- Universal Windows Platform: IL2CPP scripting back end

- ЧаВо

- Universal Windows Platform: Examples

- Universal Windows Platform: Code snippets

- Known issues

- Чеклист Мобильного Разработчика

- Experimental

- Legacy Topics

- Expert guides

- New in Unity 2020.1

- Glossary

- Unity User Manual (2020.1)

- Scripting

- Important Classes

- Important Classes - GameObject

Important Classes - GameObject

Unity’s GameObject class is used to represent anything which can exist in a Scene.

This page relates to scripting with Unity’s GameObject class. To learn about using GameObjects in the Scene and Hierarchy in the Unity Editor, see the GameObjects section of the user manual. For an exhaustive reference of every member of the GameObject class, see the GameObject script reference.

GameObjects are the building blocks for scenes in Unity, and act as a container for functional components which determine how the GameObject looks, and what the GameObject does.

In scripting, the GameObject class provides a collection of methods which allow you to work with them in your code, including finding, making connections and sending messages between GameObjects, as well as adding or removing components attached to the GameObject, and setting values relating to their status within the scene.

Scene Status properties

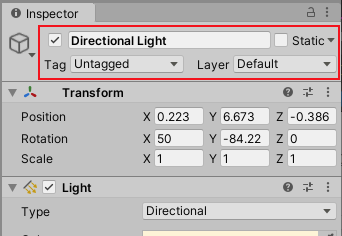

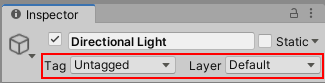

There are a number of properties you can modify via script which relate to the GameObject’s status in the scene. These typically correspond to the controls visible near the top of the inspector when you have a GameObject selected in the Editor.

They don’t relate to any particular component, and are visible in the inspector of a GameObject at the top, above the list of components.

All GameObjects share a set of controls at the top of the inspector relating to the GameObject’s status within the scene, and these can be controlled via the GameObject’s scripting API.

If you want a quick list of all the available API for the GameObject class, see the GameObject Script Reference.

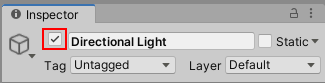

Active Status

GameObjects are active by default, but can be deactivated, which turns off all components attached to the GameObject. This generally means it will become invisible, and not receive any of the normal callbacks or events such as Update or FixedUpdate.

The GameObject’s active status is represented by the checkbox to the left of the GameObject’s name. You can control this using GameObject.SetActive.

You can also read the current active state using GameObject.activeSelf, and whether or not the GameObject is actually active in the scene using GameObject.activeInHierarchy. The latter of these two is necessary because whether a GameObject is actually active is determined by its own active state, plus the active state of all of its parents. If any of its parents are not active, then it will not be active despite its own active setting.

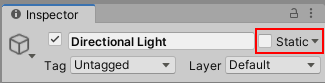

Static Status

Some of Unity’s systems, such as Global Illumination, Occlusion, Batching, Navigation, and Reflection Probes, rely on .You can control which of Unity’s systems consider the GameObject to be static by using GameObjectUtility.SetStaticEditorFlags. Read more about Static GameObjects here.

Tags and Layers

Tags provide a way of marking and identifying types of GameObject in your scene and Layers provide a similar but distinct way of including or excluding groups of GameObjects from certain built-in actions, such as rendering or physics collisions.

For more information about how to use Tags and Layers in the editor, see the main user manual pages for Tags and Layers.

You can modify tag and layer values via script using the GameObject.tag and GameObject.layer properties. You can also check a GameObject’s tag efficiently by using the CompareTag method, which includes validation of whether the tag exists, and does not cause any memory allocation.

Adding and Removing components

You can add or remove components at runtime, which can be useful for procedurally creating GameObjects, or modifying how a GameObject behaves. Note, you can also enable or disable script components, and some types of built-in component, via script without destroying them.

The best way to add a component at runtime is to use AddComponent<Type>, specifying the type of component within angle brackets as shown. To remove a component, you must use Object.Destroy method on the component itself.

Accessing components

The simplest case is where a script on a GameObject needs to access another Component attached to the same GameObject (remember, other scripts attached to a GameObject are also Components themselves). To do this, the first step is to get a reference to the Component instance you want to work with. This is done with the GetComponent method. Typically, you want to assign the Component object to a variable, which is done in using the following code. In this example the script is getting a reference to a Rigidbody component on the same GameObject:

void Start ()

{

Rigidbody rb = GetComponent<Rigidbody>();

}

Как только у вас есть ссылка на экземпляр компонента, вы можете устанавливать значения его свойств, тех же, которые вы можете изменить в окне Inspector:

void Start ()

{

Rigidbody rb = GetComponent<Rigidbody>();

// Change the mass of the object's Rigidbody.

rb.mass = 10f;

}

You can also call methods on the Component reference, for example:

void Start ()

{

Rigidbody rb = GetComponent<Rigidbody>();

// Add a force to the Rigidbody.

rb.AddForce(Vector3.up * 10f);

}

Note: you can have multiple custom scripts attached to the same GameObject. If you need to access one script from another, you can use GetComponent as usual and just use the name of the script class (or the filename) to specify the Component type you want.

If you attempt to retrieve a Component type that hasn’t actually been added to the GameObject then GetComponent will return null; you will get a null reference error at runtime if you try to change any values on a null object.

Accessing components on other GameObjects

Although they sometimes operate in isolation, it is common for scripts to keep track of other GameObjects, or more commonly, components on other GameObjects. For example, in a cooking game, a chef might need to know the position of the stove. Unity provides a number of different ways to retrieve other objects, each appropriate to certain situations.

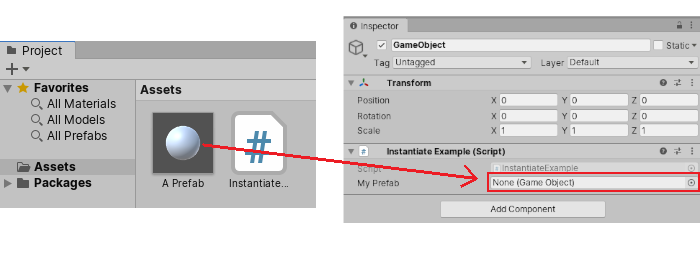

Linking to GameObjects with variables in the inspector

Самый простой способ найти нужный игровой объект - добавить в скрипт переменную типа GameObject с уровнем доступа public:

public class Chef : MonoBehaviour

{

public GameObject stove;

// Other variables and functions...

}

This variable will be visible in the Inspector, as a GameObject field.

You can now drag an object from the scene or Hierarchy panel onto this variable to assign it.

The GetComponent function and Component access variables are available for this object as with any other, so you can use code like the following:

public class Chef : MonoBehaviour {

public GameObject stove;

void Start() {

// Start the chef 2 units in front of the stove.

transform.position = stove.transform.position + Vector3.forward * 2f;

}

}

Additionally, if you declare a public variable of a Component type in your script, you can drag any GameObject that has that Component attached onto it. This accesses the Component directly rather than the GameObject itself.

public Transform playerTransform;

Соединение объектов через переменные наиболее полезно, когда вы имеете дело с отдельными объектами, имеющими постоянную связь. Вы можете использовать массив для хранения связи с несколькими объектами одного типа, но связи все равно должны быть заданы в редакторе Unity, а не во время выполнения. Часто удобно находить объекты во время выполнения, и Unity предоставляет два основных способа сделать это, описанных ниже.

Finding child GameObjects

Sometimes, a game Scene makes use of a number of GameObjects of the same type, such as collectibles, waypoints and obstacles. These may need to be tracked by a particular script that supervises or reacts to them (for example, all waypoints might need to be available to a pathfinding script). Using variables to link these GameObjects is a possibility but it makes the design process tedious if each new waypoint has to be dragged to a variable on a script. Likewise, if a waypoint is deleted, then it is a nuisance to have to remove the variable reference to the missing GameObject. In cases like this, it is often better to manage a set of GameObjects by making them all children of one parent GameObject. The child GameObjects can be retrieved using the parent’s Transform component (because all GameObjects implicitly have a Transform):

using UnityEngine;

public class WaypointManager : MonoBehaviour {

public Transform[] waypoints;

void Start()

{

waypoints = new Transform[transform.childCount];

int i = 0;

foreach (Transform t in transform)

{

waypoints[i++] = t;

}

}

}

You can also locate a specific child object by name using the Transform.Find method:

transform.Find("Frying Pan");

This can be useful when a GameObject has a child GameObject that can be added and removed during gameplay. A tool or utensil that can be picked up and put down during gameplay is a good example of this.

Sending and Broadcasting messages

While editing your project you can set up references between GameObjects in the Inspector. However, sometimes it is impossible to set up these in advance (for example, finding the nearest item to a character in your game, or making references to GameObjects that were instantiated after the Scene loaded). In these cases, you can find references and send messages between GameObjects at runtime.

BroadcastMessage allows you to send out a call to a named method, without being specific about where that method should be implemented. You can use it to call a named method on every MonoBehaviour on a particular GameObject or any of its children. You can optionally choose to enforce that there must be at least one receiver (or an error is generated).

SendMessage is a little more specific, and only sends the call to a named method on the GameObject itself, and not its children.

SendMessageUpwards is similar, but sends out the call to a named method on the GameObject and all its parents.

Finding GameObjects by Name or Tag

It is always possible to locate GameObjects anywhere in the Scene hierarchy as long as you have some information to identify them. Individual objects can be retrieved by name using the GameObject.Find function:

GameObject player;

void Start()

{

player = GameObject.Find("MainHeroCharacter");

}

An object or a collection of objects can also be located by their tag using the GameObject.FindWithTag and GameObject.FindGameObjectsWithTag methods.

For example, in a cooking game with one chef character, and multiple stoves in the kitchen (each tagged “Stove”):

GameObject chef;

GameObject[] stoves;

void Start()

{

chef = GameObject.FindWithTag("Chef");

stoves = GameObject.FindGameObjectsWithTag("Stove");

}

Creating and Destroying GameObjects

You can create and destroy GameObjects while your project is running. In Unity, a GameObject can be created using the Instantiate method which makes a new copy of an existing object.

For a full description and examples of how to instantiate GameObjects, see Instantiating Prefabs at Runtime.

There is also a Destroy method that will destroy an object after the frame update has finished or optionally after a short time delay:

void OnCollisionEnter(Collision otherObj) {

if (otherObj.gameObject.tag == "Garbage can") {

Destroy(gameObject, 0.5f);

}

}

Note that the Destroy function can destroy individual components without affecting the GameObject itself. A common mistake is to write this, assuming it will destroy the GameObject the script it’s attached to…

Destroy(this);

…whereas, because “this” represents the script, and not the GameObject, it will actually just destroy the script component that calls it, leaving the GameObject behind, with the script component removed.

Primitives

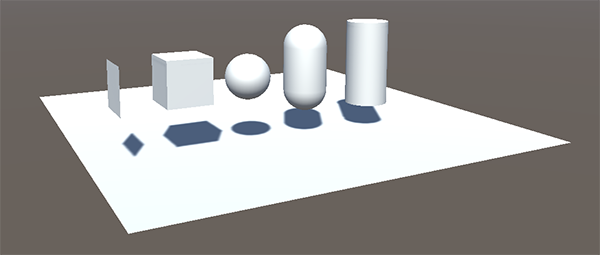

The GameObject class offers script-based alternatives to the options available in Unity’s GameObject menu that allows you to create primitive objects.

To create instances of Unity’s built-in primitives, use GameObject.CreatePrimitive, which instantiates a primitive of the type that you specify. The available primitive types are Sphere, Capsule, Cylinder, Cube, Plane and Quad.